FIRE AND SWORD IN THE CAUCASUS

[ page 176 ]

CHAPTER IX

BAKU AND THE ARMENO-TARTAR FEUD

THE accounts of the September massacres at Baku were slowly filtering into the papers while I was in Georgia, and every day news came of fresh horrors, some true, some exaggerated, some purely fictitious. So I determined to leave Georgians and Gurians and hurry to the oil city. My train was almost empty, but every train I met coming in the opposite direction was crowded with refugees flying from the town. According to some accounts the whole of Baku was in flames and half the inhabitants massacred, while according to others only the oil-fields of Balakhany and Bibi Eybat were burning. All agreed that the authorities had very few troops, but large numbers were reported on the way.

The scenery between Tiflis and Baku is beautiful in some ways, but very desolate, and the desolation increases with every mile. For a short distance after leaving Tiflis the country is fairly green and cultivated in the valleys, but the mountains are quite bare. Then we gradually descend into the vast wastes of the Transcaucasian or Karabagh steppe

[ To face page 177 ]

[caption] Camels in the Caucasus

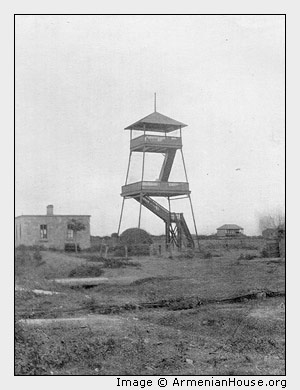

[caption] In the Karabagh Steppe. A Sleeping Tower.

[ page 177 ]

Small oases of vegetation appear from time to time, where some colony has been planted to cultivate the land, but as we near the Caspian these specks of green become ever less frequent. There are many stations, but save in a few cases there is no village or town in sight of them; they are merely stopping-places bearing the name of some spot many miles away. Close to each station I noticed some curious wooden towers, consisting of two or three platforms one above the other supported on open frameworks, with ladders going up to the top. They are used by the railway employees to sleep on during the hot weather, so as to escape the malaria, which is very prevalent throughout the Kura valley. One can hardly conceive of a more lonesome existence than that of a station official in this God-forsaken land. Such villages as we pass are incredibly primitive— groups of mud huts covered with straw or grass, sometimes mere holes in the ground hardly distinguishable above the level of the plain. Dark-skinned Tartars in blue tunics throng the stations or ride about the plain on their ambling steeds ; occasionally a team of oxen may be seen drawing a plough across the unresponsive parched soil, and a long caravan of slow-going camels passes by. Sometimes for many miles at a stretch there is no living thing in sight, only the endless wilderness where nothing grows but grey artemisia, blue delphiniums, and the poisonous Pontic absinth. In the distance to the north the purple crags of Daghestan shoot up, bold, imposing peaks, sometimes tipped with snow. Many rivers descend into the valleys from those mountains

[ page 178 ]

and also from those of Armenian highlands to the south, as if to join the Kura, but most of them are lost in the parched desert and disappear into the sands. There are, however, some broad expanses of marsh, rich in fever-breeding mosquitoes, and many deep gullies empty in summer but full of water in the rainy season.

The atmosphere is all shimmering sunshine and pitiless heat, which makes every detail of the landscape quiver as if with vitality, but a vitality malevolent to men. One has a sense of the innate wickedness of the nature of this inhospitable land, and it is easy to understand the dread with which the Karabagh steppe was regarded before the railway was built, and the many weird legends concerning it. It was supposed to be swarming with venomous snakes and equally dangerous scorpions. Tales were told of vast armies that had vainly attempted to cross it and had been swallowed up in its hideous waterless wastes. Yet in a more distant past there was here a developed civilization and prosperous cities. It is one of those countries like Persia, Albania, or Asia Minor, where civilization has gone back; the stage of agricultural and urban life has been succeeded by that of pasture, and this again by complete abandonment. Everywhere we come upon traces of buildings and irrigation canals where now hardly a blade of grass will grow. Nor would it be difficult to restore fertility to the land, and in the few spots where irrigation has been attempted, as in the German colonies and in the fields round Shemakha and Nukha good crops are raised once more, for a large part of the soil is the black mould so common in South Russia.

[ page 179 ]

The only large town which the railway passes is Elizavetpol, then quiet enough, but where Tartars and Armenians were to fight in the winter. Verst after verst we crawl down the Kura valley, sometimes in sight of the river, until Adji Kabul, where the line turns northwards between a steep rocky ridge and the sea. The Caspian is glassy and motionless ; it seems hardly a real sea at all, but rather some sulphurous pool of the Inferno. Not a tree or grass-patch in sight; the thick grey dust on the ground swirls up in clouds at every breath of air or the passage of the train ; the more distant landscape is lost in heat haze. For a few minutes we lose sight of the sea and enter a narrow cutting with high sand dunes and rocks on either side ; we soon emerge once more and steam slowly into the station of Baladjary, where the Transcaucasian and Vladikavkaz railways meet. Long lines of carriages and oil-tank trucks encumber many sidings, but while the ordinary traffic is largely suspended there are signs of feverish military activity ; the station is thronged with troops, the white uniforms and the glitter of bayonets are ubiquitous, orderlies and officers rush up and down excitedly, and several guns are being entrained. After a long wait the train leaves Baladjary, and soon a heavy black pall appears to the north. It hangs over the oil-fields of the Apsheron promontory, whence, although they are no longer in flames, volumes of black smoke are still issuing. We creep along past sordid suburbs and ruined buildings, and at last draw up in the truly magnificent station of the oil city. An immense crowd is collected on the platform, consisting chiefly

[ page 180 ]

of refugees fighting for places in the outgoing trains. More soldiers, more bayonets, more gendarmes and policemen. I secure a cab with some difficulty, at four times the usual price, for no Tartar or Armenian driver dares appear in the streets, and only Russians are available. Many people are afraid of using cabs at all unless under the escort of a couple of soldiers with fixed bayonets; but as I was neither a Tartar nor an Armenian, and did not look in the least like either, I felt I could safely dispense with such protection.

My first impression of Baku was desolate in the extreme. Grey, dreary, ill-paved streets, deep in dust, flanked by houses of grey stone or mud, machinery piled up in yards, windows closed and shuttered, few passers-by, but perpetual patrols. A certain number of more imposing edifices rise up here and there ; they are the palaces of the oil kings and the offices of the various companies. In one or two streets there are some fairly handsome shops, and then close by a wretched Tartar slum. Groups of Tartars and Armenians are gesticulating angrily and excitedly, a party of armed men is seen through a half-closed doorway, and further on a detachment of Cossacks with unslung rifles is on guard. A general sense of expectation and anxiety hangs over the town, and further developments are awaited which will add horror on horror's head.

I reach the Hôtel de 1'Europe, a gaunt, comfortless hostelry, high as to prices, low as to everything else. Here I find a number of people connected with the oil world who have left their houses, considering them no

[ page 181 ]

longer safe. I also found my friend G. B., with whom I was to travel for a considerable time.

Baku is in every sense a unique city. Its appearance, its history, its wealth, its natural features, the character of its inhabitants form an ensemble at once wonderful and terrible, fascinating and repulsive. It is situated on a hillside and round a broad, well-sheltered bay. The old Tartar and Persian quarters are on the upper slopes of the hill, and consist of a perfect labyrinth of tortuous narrow lanes and ramshackle, tumble-down houses, chiefly of mud; but there are also the remains of an old Persian fortress, a palace of the khans with some fine Oriental decoration, old walls, and several picturesque mosques and baths. The Tartar bazar is enclosed in an extremely narrow space, with booths and shops of the usual Eastern type which does not seem to change from Bosnia to India. There are fragments of Arab and Byzantine fortifications, a curious tower 150 feet high, just below the citadel, and some traces of walls emerging from the sea.

Below and around the old city a number of new quarters have sprung up to shelter the vast influx of people from all parts of the world who have flocked to Baku in the hope of making fortunes. The Tartar quarter is now separated from that of the Armenians by a row of empty houses, for no one dares to live on the borderland between the two. Some of the buildings along the quay are large and imposing, but everything bespeaks the comfortless ostentation and vulgarity of the nouveau riche, Baku, considering its immense wealth, is one of the worst managed cities in

[ page 182 ]

the world. The lighting is inadequate, the wretched horse-tram service pitiable, the sanitary arrangements appalling ; vast spaces are left empty in the middle of the town, drinking water is only supplied by sea water distilled, the few gardens are arid and thin, the dust is ubiquitous—fine, penetrating dust that gets into every nook and cranny. The country behind Baku is a very abomination of desolation, treeless and grassless. It seldom rains, in summer it is very hot, and the town is at all times exposed to sharp winds.

Eastward the Apsheron peninsula juts out into the sea, and here are situated the Black Town with the petroleum refineries, and beyond that the oil-fields of Balakhany, Sabuntchy, and Ramany ; those of Bibi Eybat are to the east of the town.

It is a trite description of every Oriental city which happens to have electric light, railways, and trams, side by side with mosques and bazars, to say that it is a mixture of East and West, and to dwell on the contrasts and incongruities of this juxtaposition. But at Baku we have both East and West in their most intense, if not most attractive, aspect. While in no Eastern city are savage passions, bloodthirsty fanaticism, and fiendish cruelty so rampant as in “ Petroleo-polis,” in few spots of the Western world, save perhaps in Johannesburg and in some American cities, is there such fierce financial competition, such mad speculation, such colossal frauds, such a thirst for gain quickly acquired, such a building-up of huge fortunes in a short space of time, and such irretrievable ruin.

Baku is a very ancient city. It is said to have been founded in the VI. century, and it rapidly

[ page 183 ]

attained to a position of great importance owing to its situation as an emporium of commerce ; it is the best port on the Caspian, and forms a most convenient point of transit to or from Persia and Central Asia. Byzantine Greeks, Arabs, Persians, Tartars, Russians, have all held sway over Baku at different times, but the Persians are those who ruled it longest and left the deepest impression. From an early period the existence of the mineral oil deposits and of natural gases was known, and frequently mentioned by mediaeval writers. The eternal flames were held in great veneration by the fire-worshippers, and pilgrims came to visit the temples on the Apsheron peninsula from all parts of Asia; one of these fanes still exists at Surakhany, though it has no worshippers. During the XVI. and XVII. centuries Baku, like the rest of Eastern Transcaucasia, was ruled by Tartar khans under Persian suzerainty. Its whole history is one long record of blood feuds and massacre. In 1722 Peter the Great, who had long coveted the city for commercial reasons and for the oil-fields, sent an expedition from Astrakhan to Derbent, which town was captured, and the following year the Russians entered Baku. Some attempt to develop the oil industry was made and fifty wells were sunk, but the workings were of a most primitive kind. Armenian settlements existed already in the Shirvan province,* but with the Russian occupation their numbers increased. In 1735, in the reign of the

-------

* Now the government of Baku; before the recent development of the oil city Shemakha was the most important town of the province.

[ page 184 ]

Empress Anne, Baku was restored to Persia, by whom it was held until 1806, when Russia re-occupied it definitely. Since then the oil industry has been greatly developed, slowly at first, but with astonishing rapidity during the last twenty years. In 1829 there were 82 naphtha pits, which rose to 136 in 1850 and to 415 in 1872, when they produced 22,581 tons. In 1858 an attempt was made to extract petroleum from the crude naphtha, and in 1863 the first refinery was founded by the Armenian Melikoff.* Armenians were indeed the pioneers of the industry, although Russians and foreigners soon rushed to Baku in large numbers. In 1871 the first well was drilled, and since then the new system has prevailed over the old. Two years later the first “spouter” or fountain was struck, ejecting vast quantities of oil, and subsequently others were discovered. The Orbeloff fountain (1877-81) was 200 feet high and produced 1,000,000 puds † a week, and the Mantasheff fountain of 1881 was more than twice as high. The total naphtha production of the Baku oil-fields rose from 25,000,000 puds in 1880 to 614,971,689 puds in 1904. At present the total capital invested in Baku amounts to between £30,000,000 and £40,000,000. Of this amount about £8,500,000 is English money. The prices for crude naphtha oscillated between 1.1 kopek per pud in 1892 and 15.7 k. in 1900 (14.67 k. in 1904);

-------

* For the statistics of the oil industry I am largely indebted to Mr. Henry, editor of the Petroleum World, who has kindly allowed me to use the figures collected in his book on Baku.

† 1 pud = 36 lbs.

[ To face page 184 ]

[caption] Baku. General View of the Bibi Eybat Oil Fields.

[caption] Baku. General View of the Harbour.

[ page 185 ]

that of naphtha residues (mazut) between 1.5 k. in 1892 and 16.4 k. in 1900 (15.04 k. in 1904); that of refined kerosene (photogene) between 7.7 k, in 1892 and 31.5 k. for export and 22.5 for home consumption in 1900 (25.42 k. for export and 20.33 for home in 1904).

The development of the oil industry has made Baku one of the chief industrial centres of Russia, and indeed of the whole world, and no other oil-fields, save those of America, are so large. The importance of the wells for Russia is incalculable. The steam navigation of the Caspian, the Black Sea, and of the whole great river system, the railways of the Caucasus and many lines in European Russia, Central Asia, and Siberia, and a number of miscellaneous industries, use liquid fuel. The Crown derives large revenues from the taxation of the oil-fields, and many tens and hundreds of thousands of families depend for the whole or part of their income on the production of the valuable liquid. But the growth of the industry is largely due to foreign enterprise, and unless we consider the Tartars and Armenians as Russians we may say that Baku is prevalently a non-Russian undertaking. Among the more important firms I may mention the following: Nobel Brothers (the Nobels are Swedes who have become Russian subjects), the Caspian and Black Sea Naphtha and Trading Company (Messrs. Rothschild), the Russian Petroleum and Liquid Fuel Co. (English), the Baku Russian Petroleum Co. (ditto, known as the B. O. R. N.), Shibaieff (ditto), the European Petroleum Co. (ditto), the Bibi Eybat Co. (ditto), Suchastniki (Anglo-

[ page 186 ]

Dutch), Mantasheff (Armenian), the Caspian Co. (ditto, Messrs. Gukassoff), the Moscow and Caucasian Co. (ditto), the Aramazd (ditto), the Baku Naphtha Industrial Co. (Russian), the Russian Naphtha Co. (ditto), the Russian Naphtha Industrial Co. (ditto). The industry is a wildly speculative one. To dig a well is a very expensive operation—it may cost £10,000 or more, and you may never strike oil at all. Large fortunes have been made or lost in a few weeks.

The whole population of Baku, including the Bailoff promontory, the White Town, the oil-fields, and the neighbouring villages, amounted before the disturbances to over 200,000. It is an extremely mixed population, composed of almost every race of East and West, and is divided as follows : 74,000 Russians (immigrants from all parts of Russia who only stay a short time at Baku), 56,000 Tartars (natives of the town and district), 25,000 Armenians (natives and immigrants from all parts of the Armenian world), 18,000 Persians (mostly immigrants for a short time), 6,000 Jews, 4,000 Kazan Tartars, 3,800 Lezghins, 2,600 Georgians, 5,000 Germans, 1,500 Poles, and many other nationalities numbering less than 1,000 each. It will be seen by these figures that a very large part of the population is fluctuating, and that only a small proportion can be set down as native or permanent. Of the latter the Tartars form the great majority; they own by far the greater part of the land and house property, including the soil where several of the oil properties are situated, whence they derive large incomes in royalties and ground rents.

[ page 187 ]

The trade of Baku, especially the shipping trade, is wholly in Tartar hands, and M. Taghieff, who laid the foundations of his fortune by selling a plot of petroliferous land, owns a whole fleet of steamers ; the money-lenders are also all Tartars. But in spite of their wealth and the business ability of a few of them, the great majority are mere primitive savages. To the Armenians above all is the development of Baku due, for they were the first to work the oil-fields on a large scale and on modern lines ; they perform a large part of the skilled labour, and among them most of the managers, engineers, as well as many capitalists, are to be found. The British public supplied a considerable share of the capital invested, and there are several Englishmen and other foreigners in prominent positions. The roughest unskilled work (chornaya rabota) is performed by the Tartars, Lezghins, and Persians ; the skilled work by the Armenians and Russians ; the management by Armenians, Russians, and foreigners. Lately, since the disorders, many of the Armenian and Tartar workmen fled, and there has been a considerable influx of Russians in consequence.

The rivalry between the Armenians and the Tartars is of ancient date, and differs little from the general rivalry of the two races in other parts of the Caucasus. The Tartars have always considered Baku as a Tartar city. The Tartar khans have ruled it for centuries, the great bulk of the native population of the whole province is Tartar, and the general character of the country until the recent influx of foreigners was mainly Tartar and Mohammedan. But the Armenians,

[ page 188]

with their superior education, their greater intelligence and push, have acquired an increasing influence in the town and the industry, and have edged the Tartars out of many professions. There are only two small Tartar oil firms, although many Tartars are interested in the business. At Baku, where they are numerically inferior, the Armenians form a majority on the town council, as the law does not allow the non-Christian races to have more than half the seats on local bodies. Even in competition with foreigners the Armenians hold their own, for while their interests on the naphtha industry are only 35 per cent. of the total, they are represented by five members out of seven on the Soviet Siezd (council of naphtha producers). There are also no Tartars on the Bourse Committee.

One fact which struck me very forcibly during my stay at Baku was the extreme bitterness of the foreign element against the Armenians ; its sympathies, save in two or three instances, seemed wholly on the side of the Tartars. This attitude, I confess, impressed me at the time, and having come to the Caucasus with an open mind, I became inclined to believe that the sufferings of the Armenians had been grossly exaggerated by the European Press, and that the Tartars were a much-maligned people. While a man like Agaieff, on whom I called, was able to make out a good case for the Tartars, Englishmen, Russians, and other outsiders were almost unanimous in their condemnation of the Armenians. Even the common Russian soldiers and policemen, when questioned as to who was to blame for the troubles, replied unhesitatingly, “ Armiane.” In a place where

[ page 189 ]

racial and religious animosities have reached a white heat it is very difficult to arrive at a fair estimate of the rights and wrongs of a controversy, and one naturally tends to trust in the judgment of foreigners who know the country well but should be free from bias. But on closer investigation I could not help coming to the conclusion that the foreigners were by no means so impartial as they at first appeared. Quite apart from the greater personal charm of the Moslem over the Armenian, the views of foreign financiers and managers are greatly influenced by the fact that they are in close commercial competition with the Armenians. If it were not for them the foreigners would soon have got the whole oil industry into their own hands, instead of being obliged to compete with capable, business-like, and energetic rivals. At the same time the Armenian workmen are much less tractable than the Tartars. They demand better food and higher wages, more comfortable lodgings, baths, reading-rooms, &c., whereas the Tartars are content with anything that is given them. The Armenians belong to workmen's societies, and if they do not get what they want they organize strikes, and even take part in revolutionary movements. The Baku strikes in the summer of 1903 are a case in point. With the Tartars, once you have their own chiefs and the Russian authorities on your side, you can do anything; but with the Armenians you must be careful. The latter, being politically more advanced than the Tartars, are more exacting. Then, since the Government instituted persecutions against them and their Church,

[ page 190 ]

they indulged in political agitation, which, if not primarily directed against

the capitalists, did cause them loss by disturbing the general conditions

of the town. This explains the attitude of the foreigners, and accounts for

their bitterness against the Armenians. One prominent Englishman said to me

that he would be glad to see the whole Armenian nation wiped out! He accused

them of every conceivable crime, of having been the cause of the whole trouble,

of being at the bottom of every revolutionary agitation, and even of having

attempted his own life. The evidence adduced in support of these charges was,

I am bound to say, quite Caucasian in its inconclusiveness, and I have never

subsequently come on a particle of proof of their truth from any source.

So much for the general situation at Baku. The account of the outbreaks I

shall reserve for the next chapter.

[ To face page 191 ]

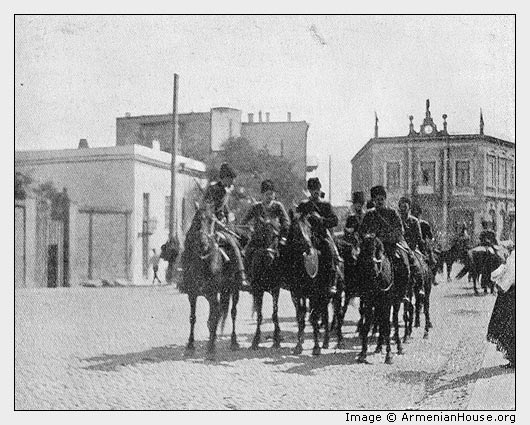

[caption] Baku. Cossak Patrol on the Quay.

[caption] Baku. The Official Residence of the Governor-General.

Table of contents

Cover and pp. 1-4 | Prefatory

note | Table of contents (as in the book)

| List of illustrations

“Chronological table of recent events in the

Caucasus”

1. The Caucasus, its peoples, and its history

| 2. Eastward ho! | 3. Batum

4. Kutais and the Georgian movement | 5. The

Gurian “republic” | 6. Tiflis

7. Persons and politics in the Caucasian

capital

8. Armenians, Tartars, and the Russian government

9. Baku and the Armeno-Tartar feud | 10. Bloodshed

and fire in the oil city

11. The land of Ararat | 12.

The heart of Armenia | 13. Russia's

new route to Persia

14. Nakhitchevan and the May massacres

| 15. Alexandropol and Ani

16. Over the frosty Caucasus | 17. Recent

events in the Caucasus | Index

| Acknowledgements: |

| Source:

Villari, Luigi. Fire and Sword in the Caucasus by Luigi Villari author

of “Russia under the Great Shadow”, “Giovanni Segantini,”

etc. London, T. F. Unwin, 1906 No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed by any means without written permission of the owners of ArmenianHouse.org |

| See also: |

| The Flame of Old Fires by Pavel Shekhtman (in Russian) |