FIRE AND SWORD IN THE CAUCASUS

[ page 191 ]

CHAPTER X

BLOODSHED AND FIRE IN THE OIL CITY

“ Gyre-circling Spirits of Fire ”

THE story of the various Baku outbreaks has been told in the Press,* but the accounts have been fragmentary and often inaccurate, so that I think it advisable to set forth the events in their proper order. The Baku pogromy form part of the bloody drama of Armeno-Tartar hostility, and indeed, the February massacre was the first occasion on which the two races actually fought on a large scale. But they are also part of that wider feud between modern ideas and Asiatic barbarism which is in progress all over the East and in Russia itself. The struggle for freedom now being fought in the Tzar's dominions is but a conflict between the Asiatic and mediaeval autocracy and latter-day progress.

It is not easy to obtain reliable information when passions have been roused to such a pitch of savagery as at Baku, and one needs to be very careful in sifting

-------

* Mr. Henry, in his Baku, tells the story of the Baku troubles with much detail, but since he wrote fresh facts have come to my notice modifying some of his statements.

[ page 192 ]

the vast mass of evidence supplied to the inquiring stranger, all of it from more or less prejudiced sources, and to clear the ground of false charges and absurd exaggerations. In the first place a few dates must be established so as to make the sequence of events clear. In July, 1903, strikes broke out among the Russian and Armenian workmen on the oil-fields—strikes which were mainly economic but had a political arriére pensée, as was the case with other strikes that year in various parts of Russia. They marked, indeed, the beginnings of the revolutionary movement. Some derricks had been set on fire, and the general state of Baku was giving cause for grave anxiety ; General Odintzoff was then Governor. In August the Assistant-Minister of the Interior, General von Wahl, arrived to inquire into the situation.

Prince Golytzin, who had been busy carrying out his anti-Armenian policy, had a few weeks before executed the confiscation of the Church property ; in October his life was attempted. Early in 1904 Prince Nakashidze, a Georgian noble, who as Vice-Governor of Erivan had been actively implicated in the said confiscation, was appointed Governor of Baku. His arrival coincided with a recrudescence of Armeno-Tartar hostility, and an outbreak seemed imminent at that time, so that many Armenians sent their families away from the town. In July, 1904, Prince Golytzin left the Caucasus for good and went to St. Petersburg. Towards the end of the year Prince Nakashidze was summoned to the capital, where he had several conferences with his former chief, and subsequently returned to Baku. Excitement in the

[ To face page 193 ]

[caption] Baku. A Quiet Drive with a Soldier on the Box.

[caption] Bibi Eybat Oil Fields. The Ruins.

[ page 193 ]

oil city and the hatred of the two races increased, and the Governor did nothing to reconcile them. On the contrary, he was perpetually talking of an Armeno-Tartar pogrom as imminent; he openly encouraged the Tartars, and treated the Armenians with marked coldness. When a deputation of Armenians came to express their fears and ask him for protection, his only reply was, “ Do not you shoot and no one will shoot at you.”* In the meanwhile a number of murders of Armenians, attributed to Tartars, had been committed in the Shemakhinka street, and, on the other hand, several mutilated corpses of Tartars, supposed to have been murdered by Armenians, were discovered under the snow which had just melted away. There is a strong presumption that the police was at the bottom of these affairs, which it had instigated with a view to promoting Tartar-Armenian hatred, but I cannot say whether the suspicion is well-founded. The authorities were perpetually telling the Tartars that the Armenians were meditating a massacre of Mussulmans, and that they should be on the qui vive. Early in February a Tartar shopkeeper named Gashum Beg, who had assaulted several Armenian boys and girls, was attacked by an Armenian and wounded, but he succeeded in killing his assailant. He was subsequently arrested, and as he was trying to escape a soldier of the escort, also an Armenian, shot him dead.† The assailant proved to be a member of the

-------

* Senator Kuzminsky's report on the February outbreak,

† According to a Tartar version the soldier whispered to Gashum Beg that if he tried to escape he would be allowed to get away, and the moment he did so fired on him. The Armenians say that the idea of escape was not suggested.

[ page 194 ]

revolutionary committee, but the Armenians deny that that association ordered him to kill Gashum Beg, and state that he had been deputed to do so by the family of one of the boys he had assaulted. A relative of Gashum Beg's, a rich Tartar named Babaieff, determined, according to the Tartar custom of vendetta, to avenge him, and a few days later tried to shoot an Armenian in the courtyard of the church, who had been pointed out to him as the man who had killed Gashum Beg ; but he failed, and in the émeute which ensued, another Armenian killed him. This deed caused great excitement in the town, and Prince Nakashidze summoned some Armenian journalists to his Chancery, and delivered them a long discourse on the dangers of an Armeno-Tartar pogrom. He declared that if the Tartars did rise against the Armenians he would be powerless to defend them, as he had not enough troops, and the police were unreliable, many of them being Tartars. In fact one of the said Armenians told me that parts of this speech corresponded almost word for word with the report which the Governor made after the massacre, which suggests that he had foreseen the whole affair.

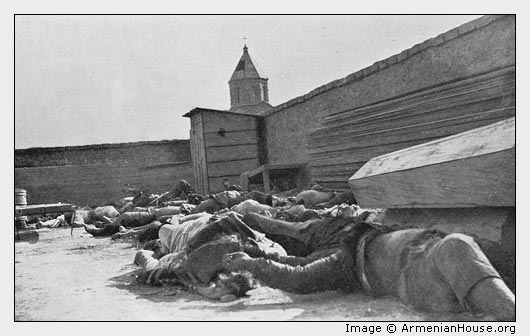

The body of Babaieff was carried in procession through the Tartar quarter, and exposed to view. Had Prince Nakashidze wished to prevent trouble he would have stopped the procession ; the sight of the murdered man roused the Moslems to fury, and on the 19th of February they proceeded to

[ page 195 ]

massacre every Armenian they came across. The Armenians defended themselves as best they could, but the Tartars were much more numerous and better armed. The authorities remained absolutely passive, and to the frenzied appeals for help which Prince Nakashidze was constantly receiving from hard-pressed Armenians besieged in their own houses, he replied that he had no troops and could do nothing, although as a matter of fact he had 2,000 men. He was seen driving about the town openly encouraging the Tartars, and slapping them on the back; and on one occasion, happening to see some too officious soldiers disarming a Tartar, he ordered them to give the man back his rifle, which of course they did ! M. Adamoff, one of the richest Armenians in Baku, was besieged for three days in his own house, and being a first-rate shot he killed a number of his assailants with his own hand; at last he and his son were shot dead, the Tartars set fire to the house, rushed in and butchered all the inmates. A similar fate befell Lalaieff, another rich Armenian, who defended himself until ammunition gave out, after which his house was burnt and the whole household killed. To his appeals for help the Governor made no reply, but came himself when all was over.

At last on the fourth day, when both sides were exhausted, the pogrom came to an end, after some 300 to 400 people had been killed.* The Tartar Sheikh-ul-Islam arrived from Tiflis and paraded the town in company with the Armenian bishop, and a

-------

* According to the official accounts the Armenians killed were 218, the Tartars 126; possibly the numbers were somewhat larger.

[ page 196 ]

sort of peace was patched up. The Sheikh-ul-Islam, a worthy, well-meaning old man, but without much influence over the more turbulent elements of his people, preached a peace sermon in the Armenian cathedral, while the bishop preached in a similar strain in the mosque. The cooler heads on both sides were beginning to see that the chief responsibility lay with the Government, but the race hatred was now so bitter that no lasting reconciliation was possible.

For some months things remained comparatively quiet, although isolated murders were very frequent. Both Armenians and Tartars armed themselves, but the former did so on a larger scale, for they had had such experience of the Government’s hostility that they felt they now had only themselves to rely on. The revolutionary committee displayed great zeal in collecting money both from the Armenians and the foreign firms who paid it blackmail, and in smuggling arms and explosives into the town from Moscow. The Tartars, thinking themselves secure in the Government’s favour, were less active. An official inquiry into the outbreak was conducted by Senator Kuzminsky, but its findings were not published until early in this year, and none of the guilty were punished. The Armenians, however, took vengeance into their own hands, and on May 24th Prince Nakashidze was blown up by a bomb. As for his own guilt in this matter there can, I think, be no doubt whatever. The direct responsibility of Prince Golytzin is more questionable, for he had left the Caucasus several months before the Baku outbreak ;

[ To face page 197 ]

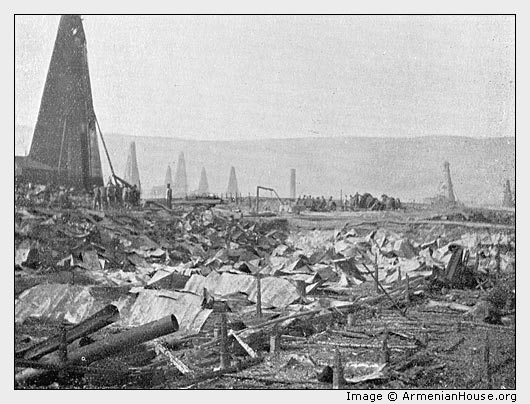

[caption] After the Fires at Bibi Eybat.

[caption] Baku. Ruined Derricks at Bibi Eybat.

[ page 197 ]

but the troubles were unquestionably the direct outcome of his own policy, and he may have given suggestions to Prince Nakashidze when the latter was in the capital.

The impunity of the Baku massacres encouraged the Tartars in other parts of the country. An account of the outbreak at Nakhitchevan, which was the outcome of the Baku disturbance, will be given in another Chapter. In the summer things began to appear critical at Shusha, a town of 35,000 inhabitants, situated high up among the mountains of the Elizavetpol Government. The population is equally divided between Tartars and Armenians, the latter occupying the upper part of the town. The fighting in other places was producing dangerous excitement also at Shusha, although a conciliation committee had been formed, which managed to keep things quiet for some time. About the middle of July a number of Armenians, travelling in omnibuses between Ievlakh (a station on the Tiflis-Baku line) and Shusha, were set upon by Tartars and plundered. The Shusha revolutionary committee and the more violent elements of the Armenians urged that it was now time to attack the Tartars, but for a few weeks more peaceful councils prevailed, although both sides were preparing for the struggle.

Throughout August fresh collisions occurred between members of the two races along the Ievlakh-Shusha road, especially in the neighbourhood of Agdam. On the 20th a Tartar was murdered at Shusha, for which the Armenians were held responsible, and on the same day a fight occurred at Vank.

[ page 198 ]

On the 29th three Armenians were murdered near Shusha, and at midday another came into the town showing the wounds inflicted on him by the Tartars. In the afternoon firing on a large scale began, which appears to have been started by the Armenians. An attempt was made to bring about a meeting between the Armenian Bishop Ashost and a prominent Tartar named Javat Aga Jehanghir and other notables of both communities to restore peace. But the meeting never took place, as neither side trusted the other. Shooting went on uninterruptedly for three days, and on the 31st incendiarism began. The Armenians set fire to the few Tartar houses in their own quarter; the Tartars did the same to the Armenian quarter. A wind favoured the flames, and soon some four hundred houses, including all the best in the place, as well as the shops and the industrial establishments, were blazing ruins. The Armenian church of Akuliatz, which had been captured by the Tartars, was desecrated in an unspeakable way and used as one of their chief strongholds. Thousands of armed and mounted Tartars flocked to Shusha from the neighbourhood, but the Armenians held a strong position commanding the chief road by which they came, and thus prevented most of them from entering the town. On the 1st of September a second attempt at conciliation was more successful, and it was arranged that a procession of members of both races, headed by Javat Aga and Bishop Ashost, should visit the Armenian quarter, and another, led by the Archimandrite Ter-Mikelian, the Tartar Casi, and the Russian Vice-Governor of Elizavetpol, who had just arrived,

[ page 199 ]

should visit the Tartar quarter. But although this programme was duly carried out, firing recommenced that same night with redoubled fury. The Tartars determined to destroy the Armenian quarter and attacked it vigorously, but the Armenians replied with a heavy fire, threw some bombs, and even produced an old cannon, which burst after a few shots, but caused great consternation among the assailants. The Vice-Governor then appealed to the Tartars, “ not as an official, but as a man and their guest,” to put an end to the bloodshed. On the 2nd the Moslem chiefs sent a messenger to the Armenians, and finally a peace conference was held at the Russian church. Tartars and Armenians publicly embraced one another and swore eternal friendship—until next time. Prisoners were exchanged, as between properly constituted belligerents. The number of killed and wounded amounted to about 300, of whom two-thirds were Tartars, for the Armenians were better shots and also enjoyed the advantage of position. The damage is estimated at from 4,000,000 to 5,000,000 roubles. The troops, of whom 350 were available, seem to have done nothing at all while the fighting was going on, but the military band performed to celebrate the conciliation!

The news of the Shusha fighting spread all over the country, and increased the agitation at Baku, which was now to witness a replica on a larger scale, of the February massacres. After the murder of Prince Nakashidze martial law was proclaimed, and a Governor-General * was appointed in the person of

-------

* The Russians apply the title of General-Gubiernator both to a Governor-General of an important region which includes several governments (gubiernia), such as Poland, Finland, or the North-West provinces, and to a military governor appointed to carry out martial law.

[ page 200 ]

General Fadeieff, the victor of Kars. The new Viceroy of the Caucasus was much better disposed towards the Armenians than his predecessor, and the Church property had now been restored. But many of the minor officials and police were still Golytzin's creatures, and at Baku the authorities refused to recognize the danger of the situation. Only a few days before the September outbreak General Fadeieff issued 16,000 permits to carry arms, and when a committee of oil producers called on him to represent the seriousness of the situation and to ask for protection, his Excellency complacently replied that everything would go off quietly, and that all was for the best in the best of all possible Bakus. General Fadeieff is not accused of having promoted the second outbreak, nor of having encouraged the Tartars, but he took no precautions to prevent trouble, although the garrison had been increased to 6,000 men.

The Social-Democrats, chiefly Russian workmen, now began to agitate again and make insistent demands for political liberty and economic improvements. The Armenian and Socialist committees worked apart, but they both had a common desire for a constitutional Government. The Armenian workmen were also demanding improvements in the conditions of labour, and their committees, although primarily political, voiced these demands. About the end of August a tramway strike broke out and the

[ page 201 ]

service was suspended for a few days. Then by order of the. Governor-General it was resumed, and soldiers were placed on the cars for protection. The strikers made a demonstration, a few shots were fired, and some Tartars were hit by accident. Further firing on a larger scale broke out in other parts of the town on the 2nd of September. The Tartar and Armenian quarters were now separated, as I said before, by a row of empty houses, so that Baku was divided into two armed camps. Fighting soon became more general, and a few houses were set on fire. But nothing very serious occurred in Baku itself, for General Fadeieff, once the disorders had actually broken out, did his best to stop them, and his troops prevented the Tartar villagers, who had assembled in great numbers outside, from coming into the town.

Far worse was the situation on the oil-fields. Large bodies of Tartars, as soon as the news of the Baku fighting arrived, gathered together and conferred with their chiefs at Balakhany and Ramany, where they were joined by others from the villages.* The Armenians, expecting an attack, concentrated in certain positions. During the night the Tartars set fire to the Armenian oil properties at Balakhany and Ramany ; the derricks, being of wood and impregnated with naphtha, burnt like tinder, and the adjoining buildings were soon in flames. The fires also spread to other non-Armenian properties, and soon a huge cloud of smoke hung like a pall over the

-------

* There are several Tartar villages on the Apsheron peninsula among the oil-fields, and others just outside.

[ page 202 ]

oil-fields, with tongues of fire darting up from the burning derricks. Desperate fighting took place wherever Tartars and Armenians met, but this time the former did not have such an easy job as in February. The attack on the Armenians at the Baku Naphtha Producers' Association was beaten back with loss, and numbers of Tartars were shot down by the Cossacks at the Va Wotan works. More fighting occurred on the 5th near the Sabuntchy hospital, where 2,000 Armenians and some Cossacks were collected, but it was not of a very serious nature. Numbers of isolated Armenians were caught by the Tartars while trying to escape and shot or cut to pieces. Some were induced to leave their hiding places by promises of safety, and then brutally murdered. At the Melikoff works several Armenians who had taken refuge in a house were burnt to death with kerosene pumped in by the Tartars. No quarter was given on either side, and neither age nor sex was spared. But amid these deeds of savage cruelty there shine also deeds of magnificent heroism. The way in which some Armenians brought women and children to places of safety or got water and provisions for the besieged under a heavy fire was beyond all praise. Three Englishmen were besieged at Zabrat several days, until relieved by the British Vice-Consul, Mr. Leslie Urquhart; but their danger was, of course, much less than that of the Armenians, for the Tartars had no feeling against any foreigners. In the meanwhile fighting and incendiarism had broken out on the Bibi Eybat oil-fields. The Pitoieff, Mantasheff, and other Armenian properties were

[ To face page 202 ]

[caption] Baku. Corpses in the Cemetery.

Photo by a Baku photographer.

[ page 203 ]

set alight, and the properties of the English firms “ Oleum ” and B. O. R. N. were also damaged. As the waterworks buildings were on fire it was impossible to put out the flames, and the detachments of Cossacks and sailors from the Caspian flotilla were unable to keep the Tartars in check. Several vessels full of armed Tartars appeared off the coast, but most of them were prevented from landing; one of these ships was said to have come from Persia. The slaughter at Bibi Eybat was much less than at Balakhany, and only a few Armenians were murdered. Various properties were invaded by Tartars, but most of the Armenians, who were not numerous, succeeded in escaping.

At last reinforcements began to arrive from Tiflis and Rostoff, and artillery was got into position, both in the oil-fields and in the town ; the troops acted with considerable energy, greatly to the disgust of the Tartars, who expected to find them on their side, or at all events that they should remain neutral. The Governor-General issued a decree that if shots were fired from any house it was to be instantly demolished with cannon. Order was thus gradually restored, although excitement was still so high that it was doubted whether it was not merely a lull before a new storm. The total number of killed amounted to about 600, and the tale of murders continued with undiminished vigour even after things had quieted down. As usual the authorities committed many mistakes, which tended to increase rather than allay the disturbances. A large house, in which the British and Italian Vice-Consulates and a number

[ page 204 ]

of offices and apartments are, was riddled with shots simply on a vague rumour, which afterwards proved untrue, that somebody had fired a revolver from one of its windows. When an Armeno-Tartar reconciliation committee called on the Governor-General with a view to concerting measures for peace, he kept them for nearly two hours talking about his own exploits at the siege of Kars ! Throughout the whole affair it was clear that the authorities did not really control the situation, and they could only pray for the reconciliation of the belligerents. They expected that Tartars and Armenians should make peace while they stood by to see fair play, but they were almost always incapable of punishing infractions of the agreement, so that public order came to be dependent on the wishes of the two races.

When I arrived at Baku the flames had burnt themselves out, and fighting had ceased. Over 10,000 soldiers were in the town and immediate neighbourhood, and others were expected. No one was allowed out after 8 p.m., but every night shots were heard, and every morning fresh corpses were found. Some of the oil producers wished to recommence work, but the precarious situation rendered this impossible. The Armenians dared not start from fear of the Tartars, and the Tartars from fear of the Armenians ; many of the Russian and Persian workmen had fled in terror, and those who remained refused to return to the oil-fields unless they were properly protected. Both the Armenian and the Russian revolutionary committees issued proclamations stating that work must not recommence until

[ page 205 ]

the lives of the men were guaranteed and their general conditions improved. The Armenian committee, indeed, threatened to murder all the managers who should start work before these demands were complied with. The English were particularly incensed at these threats, and one of them actually accused the Armenian oil producers of having inspired the menaces because, being themselves unable to begin work, they did not wish their foreign competitors to get ahead of them. I could not obtain any evidence as to the truth of this preposterous charge. On the other hand, the Armenian paper, the Baku, made equally wild accusations against some English managers, who, they said, had handed over their Armenian employees to the Tartars, lest the latter should set fire to the properties. Every day there was some fresh excitement, meetings of revolutionary committees and of industrial associations, threats, charges and counter-charges, wild rumours, arrests, discoveries of bombs, threatening proclamations, violent articles in the Baku and the Kaspii, and general panic.

I visited the premises of several oil companies at Bibi Eybat soon after the fires, and the spectacle presented simply defies description. The road from Baku to the oil-fields is flanked by a series of low sheds, workmen’s cottages, and small shops. On nearing Bibi Eybat the derricks begin to appear— curious pyramid-shaped wooden towers. A few larger buildings mark the entrance to the various oil properties. On entering the first of these a most appalling scene of destruction met my eyes. Out of the 200

[ page 206]

derricks of Bibi Eybat, 118 had been destroyed, and the majority of the other buildings were heaps of black ruins. The whole area was covered with debris and wreckage, thick iron bars snapped asunder like sticks, or twisted by the fire into the shape of coiled-up serpents and fantastic monsters; great sheets of iron torn to shreds as though they had been paper, broken machinery, blackened beams, fragments of cogged wheels, pistons, burst boilers, miles of steel wire ropes, all piled up in the wildest confusion, workmen's barracks, offices, and engine-houses razed to the ground. Everywhere streams of thick-oozing naphtha flowed down channels, or formed slimy pools of dull greenish liquid; the whole atmosphere was charged with the smell of oil. A few workmen were going about trying to clear away some of the rubbish, or find bits of iron-work that might be of use. It was more like some frightful nightmare than a reality.

Yet when one comes to inquire into the actual damages they do not seem to be quite so enormous as one would think, or as they were at first estimated. The earliest reports put the figure at £15,000,000; subsequent estimates reduced it to £10,000,000, £5,000,000, £3,000,000; and now, according to the most reliable, it cannot much exceed £2,000,000 or £2,500,000. Of this amount a little over one-tenth represents the English losses. Outsiders unacquainted with the conditions of the industry imagined that once the oil wells were set alight they went on burning until the whole of the underground deposit was consumed. But as a matter of fact nothing of the kind could possibly happen. The oil has to be extracted from a

[ To face page 206 ]

[caption] Baku. Tartar Workmen.

[caption] Baku. Armenian Workmen Outside the Htel de l’Europe.

[ page 207 ]

considerable depth—500 to 1,500 feet—so that only what is actually on the surface can burn at all. Of course all the woodwork of the derricks burnt very easily; machinery and buildings were thus destroyed, and the huge naphtha and kerosene reservoirs were also burnt. The greater part of the capital invested in the oil trade is spent in sinking the wells, and so of course is not lost. Much of the machinery too was old and obsolete, and would have had to be scrapped in any case in a year or two, so that its destruction was a less serious loss than one might think. Far graver was that caused by the cessation of production, for with the anarchy then prevailing it was impossible to do anything for some months, and even now the production is less than it is in normal times.* Dearth of labour is one of the chief difficulties ; the workmen demand higher wages and that their lives should be insured, for which heavy premiums must be paid. Even so it is very hard to get men to come at all. The whole industry has been thrown on its beam ends, and it requires drastic remedies to be replaced on a satisfactory basis once more. If the Government were in a position to guarantee order, prosperity could be restored to Baku in a very short time. The large oil producers can afford to wait until things improve, and no doubt by raising the price of oil they can more than recoup themselves for their losses apart from any

-------

* Practically there was no production in September and October; in November work recommenced, but on a small scale, and the railway strikes in that month and in December again paralyzed the industry. In January 30,000,000 puds were produced against 50,000,000 per month in normal times.

[ page 208 ]

compensation they may get from the Government. But the smaller industriels and the shareholders are in sore straits, and many who were comparatively rich men are now ruined.

Table of contents

Cover and pp. 1-4 | Prefatory

note | Table of contents (as in the book)

| List of illustrations

“Chronological table of recent events in the

Caucasus”

1. The Caucasus, its peoples, and its history

| 2. Eastward ho! | 3. Batum

4. Kutais and the Georgian movement | 5. The

Gurian “republic” | 6. Tiflis

7. Persons and politics in the Caucasian

capital

8. Armenians, Tartars, and the Russian government

9. Baku and the Armeno-Tartar feud

| 10. Bloodshed and fire in the oil city

11. The land of Ararat | 12.

The heart of Armenia | 13. Russia's

new route to Persia

14. Nakhitchevan and the May massacres

| 15. Alexandropol and Ani

16. Over the frosty Caucasus | 17. Recent

events in the Caucasus | Index

| Acknowledgements: |

| Source:

Villari, Luigi. Fire and Sword in the Caucasus by Luigi Villari author

of “Russia under the Great Shadow”, “Giovanni Segantini,”

etc. London, T. F. Unwin, 1906 No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed by any means without written permission of the owners of ArmenianHouse.org |

| See also: |

| The Flame of Old Fires by Pavel Shekhtman (in Russian) |