FIRE AND SWORD IN THE CAUCASUS

[ To face page 209 ]

[caption] Mount Ararat from the North.

Photo by Kiknadze of Erivan.

[ page 209 ]

CHAPTER XI

THE LAND OF ARARAT

UNTIL a few years ago the only railway of importance in Transcaucasia was the trunk line across the isthmus from Baku to Batum. But in 1902 a new and important line was completed going from Tiflis in a southerly direction. It had two main objects, one wholly strategic, the other partly strategic and partly economic. The first was to establish railway connection with the fortress of Kars, Russia's advanced post towards Asia Minor; the other was the “peaceful penetration” of Persia. The Kars branch was completed first; the Persian frontier has been reached only a few months ago. The new route is an interesting one in many ways. It passes through some of the most beautiful scenery in the Caucasus ; at its culminating point it is higher than any railway in Europe, and is indeed one of the highest in existence ; it traverses the high tableland of Armenia, which is historically one of the most interesting countries in the world ; it skirts the foot of Mount Ararat, the view of which is worth the whole journey from London to Erivan; and lastly it takes us to the Persian border,

[ page 210 ]

and will eventually be the means of opening up Northern Persia to Western influences.

The distance from Tiflis to Erivan is 352 versts, or about 230 miles, but the train takes sixteen hours to cover it. Russian railways are proverbially slow, the Caucasian lines are the slowest in Russia, and the Tiflis-Erivan line is the slowest in the Caucasus.

For the first few miles the line descends the Kura valley and then abruptly turns to the south towards the mountain ranges enclosing the Armenian plateau. We enter the long deep gorge of Sambak in which the train is engulfed for many hours. The steep hillsides are well wooded, with splendid forests now ablaze with the most brilliant hues of autumn, and the swirling Dabeda Chai roars down below. The villages are few and far between, but there are on every hill-top and in every open space remains of old castles and picturesque monasteries and churches, in some places of whole towns, for this country, now so thinly inhabited, was once highly civilized and well populated. There is something attractively mysterious about these forgotten lost cities, half buried in the forest; they must have witnessed many a scene of dramatic horror, for horrible Caucasian history has ever been, a record of fierce fighting, savage passions, black treachery, blind fanaticism, sublime heroism, always ending in blood and destruction, from the earliest times down to the present day, and the Caucasian book of blood is not closed yet—far from it.

At Karakliss the gorge opens out into more smiling scenery; there is bright sunlight on the woods, and

[ page 211 ]

gleaming streams, and cool greensward. Under a more civilized and progressive régime this spot would have soon been turned into a pleasant Kurort for the people of burning Tiflis to fly to in August, with hotels, villas, shops, and bands. As it is there is nothing but a small village and some cottages where rooms are let in the summer. The state of security leaves much to be desired; brigandage flourishes, and a few days after I passed through, a train was held up and a large sum of money carried away. From Karakliss a road leads to Delijan and on to Lake Gok Chai, the largest and most beautiful in the Caucasus. The line now ascends still steeper heights, and vegetation on the mountain slopes soon disappears. As we proceed southwards the Armenian type and costume becomes more and more predominant.

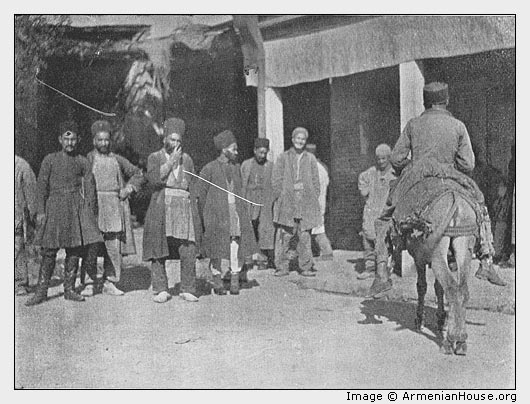

The stations are built of stone and seem to be of extraordinary solidity. At one of them I got out to take a photograph of a picturesque group of blue-clad, fur-capped Armenians. They were pleased and amused by my performance, but when I returned to my compartment, I was followed by a gendarme. Very politely and deferentially he asked me what I was photographing; I replied with truth that I had been snapping Armianskie tipy.

“ But photographing is forbidden on this line.”

“Why?” I asked.

“ I do not know, but I suppose for some political reason.”

“ I am very sorry, but I did not know.”

“ Will you give me the plate ? ”

“ Alas ! ” I replied, “ but I have no plates.” (I

only

[ page 212 ]

used films.) That was quite beyond him. He did not know what plionki (films) were. I tried to explain : “It is absolutely impossible for me to take out that film until I have finished the whole twelve, and I am only at No. 5.”

“Very well; will you kindly tell me your name, your father's name, your profession, your nationality, your habitual abode, where you are going, and what hotel you will stay in ? ”

I supplied these details, which were duly set down in a notebook which the uniformed gentleman kept under his cap ; he then saluted and retired, and I heard no more of the affair. The real reason of the prohibition is no doubt the fact that the Tiflis-Kars line is a strategic railway and is treated as though it were a continuous fortress ; no objections were raised to my taking photos on the Alexandropol-Erivan-Nakhitchevan branch. This was my first and only collision with the celebrated Russian police during the whole of my tour. It was typical of Russian methods that my violation of the law should have had no consequences. In Germany if a thing is strengsten verboten it really is verboten, and woe to the man who disregards the warning. But the Russian equivalent, strogo vospreshtchaietsia is a much milder prohibition, and if you talk nicely to the guardians of the law, or are a stranger, or a celebrity, or ready to pay a small bribe, you may do what you like and have no further trouble.

The train creeps up the mountain side, enters a long tunnel, in the middle of which is the highest point along the line (7,355 feet above the sea), and then

[ To face page 212 ]

[caption] Armenian Types.

(The Photo for which I was nearly arrested.)

[ page 213 ]

descends on to the Shirak plateau. We are now in the true Armenia, the original home of the Haik people. On all sides we are encircled by a barrier of bare, forbidding rocks, but the valleys are to some extent cultivated. The air is delicious, and quite cold in the early morning, but it gets very hot in the middle of the day in spite of the great height and the season of the year—we are now at the beginning of October. Brown undulating plateaux, naked grey rocks piled up by volcanic action, patches of trees and grass, and fields of corn. Then suddenly through a gap in the nearer mountains, the blue-grey snow-capped summit of the Alagöz rises up 13,436 feet high. Besides Ararat it is the only mountain with eternal snows in Russian Armenia. By a series of sharp curves the line descends to Alexandropol, a large town and fortress, which is the junction where the Kars and Erivan branches meet. I did not stop here on my way out but pushed on to Erivan. The landscape becomes ever broader and larger, as the vast rolling uplands spread out, an endless vista of golden earth, earth and atmosphere of that shimmering hue only seen in the East. Then suddenly through another break in the circle to the south we see right across the plain, and Ararat appears in all its glory. I have never seen such an imposing mountain before or since, in the Alps or in the Caucasus. It rises sheer up out of an immense plain, which forms an exquisite foreground like a rich Persian carpet, of green, brown, yellow and red grasses, wastes of golden sand, and oases of poplars and vineyards; the great mountain shows up like some airy structure of a dream, against the

[ page 214 ]

parched plain. The circle of heights framing the picture never rises to more than 10,000 feet, while Ararat is 16,916 and dominates them all. It is this isolation which makes it so magnificent. The great peaks of the Alps are surrounded by other peaks nearly as high; Mont Blanc is but primus inter pares, and even the bolder form of the Matterhorn is challenged by powerful rivals. But Ararat is an undisputed autocrat, towering far above the pigmies around him, who serve but to exalt and glorify him. For weeks I lived in sight of this mighty giant; every day he assumed a new aspect, and I was never tired of feasting my eyes on his kingly beauty.

Ararat is formed of two summits, unequal in height and different in form ; Great Ararat, a vast, rounded mass, purply blue in colour, diaphanous and velvety in texture, surmounted by a magnificent dome of ice and snow, with glaciers creeping down the sides; and Little Ararat, a sharp peak only tipped with snow at the summit. Between the two is a deep depression, where the post of Sardar Bulagh (“the Governor's Fountain”) is situated, the best point whence to begin the ascent.

“ But most of all,” writes Mr. H. F. B. Lynch, “as we realize the vision, which in the noblest shapes of natural architecture, the dome and the pyramid, fills the immense length of the southern horizon and soars above the landscape of the plain, the essential unity of the vast edifice and the correspondence of the parts between themselves are imprinted upon the mind. If Little Ararat, rising on the flank of the giant mountain, may recall, both in form and in position, the

[ page 215 ]

minaret which, beside the vault of a Byzantine temple, bears witness to a conflicting creed, this contrast is softened in the natural structure by the similarity of the processes which have produced the two neighbours, and by their intimate connection with one another as constituents in a single plan."

Ararat is of volcanic origin, and although as a volcano it is now extinct, there are vast deposits of hot water within its subterraneous hollows, and at times torrents of boiling mud have been ejected, dealing death and destruction to the villages on the mountain slopes. Earthquakes, too, are very frequent in this region, one of the most terrible being that of 1840, in which the Armenian village of Akhuri was completely destroyed. The halo of legend and historic tradition with which the mountain is surrounded invests it with mystic sanctity. The story of the Ark is still a living belief among the Armenian and Mohammedan races inhabiting the Ararat country; the Armenians, indeed, believe themselves to be the first race of men which grew up in the world after the Flood. The town of Nakhitchevan is said to have been founded by Noah immediately after leaving the Ark, and its name is supposed to mean “ the first home.” The Persian name for Ararat, Koh-i-Nuh, means Noah's mountain. Almost the whole history of the Armenian people centres round Mount Ararat, which stands now at the confines of the three great States—Russia, Persia, and Turkey—and was in the past the meeting-point of Persians, Turks, and Armenians. Its various names—Ararat meaning high, Masis or sublime—are

[ page 216 ]

symbolical of the overpowering impression which it has always made on the people who dwelt in its shadow.

On climbers, too, it has exercised a great fascination, and has been ascended several times; the first ascent was by the German, Parrot, in 1829; Professor Abich ascended it in 1845, the Russian General Khodzko in 1850, and remained five days on the summit in order to carry out a survey. Mr. James Bryce and Mr. H. F. D. Lynch are among the best-known English climbers who achieved the feat. It is said not to be a very difficult climb for an experienced mountaineer, but it is extremely long and tiring.

Towards evening I reached Erivan, the terminus of one branch of the line (the Nakhitchevan-Djulfa branch starts off from a station before Erivan). Immediately on my arrival I felt that there was something up. There was excitement among the station officials, agitated soldiers and gendarmes were rushing about, and I had considerable difficulty in procuring a vehicle. I drove towards the town (the station, as is usual in Russia, is several miles outside), and on two occasions I found the way blocked by patrols, so that the cab had to make a detour. On demanding the reason I was told that there was an Armeno-Tartar disturbance. At last the inn was reached—the Hôtel d’Orient. Here a crowd of soldiers, policemen, Cossacks, and others were gathered, and two sentries with fixed bayonets stood on guard at the door. This was due to the presence of Prince Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, who

[ To face page 217 ]

[caption] Erivan. Carts in the Bazar.

[caption] Erivan. Shops.

[ page 217 ]

had been nominated Governor-General of Erivan since the previous June. As his appointment was only a temporary one he had no fixed residence, but was staying at the hotel. It was curious to see Russian military proclamations posted about the town bearing the signature “ Napoleon.”

The whole town was in a state of tumult, as the Tartars and Armenians had begun fighting that very afternoon, and Prince Napoleon was busy restoring order. I had an introduction to an Armenian gentleman, who was Inspector of Taxes, and I wished to call on him immediately, so as to learn something of the situation. I asked the hotel porter for his address, but was told that I could not go to the house, as I should have to pass through the Tartar quarter where fighting was still in progress. I tried to get a policeman to escort me, but without success ; then I came on a group of peasants and townsmen going in that direction, and I followed them up the Akstafievskaya, the principal street of Erivan. I had not walked a hundred yards when a detachment of dragoons blocked the way. Expostulation was useless, as the soldiers began to ride their horses on to the side-walk, so I had to return to the inn. However, I managed to go out later, but the excitement was soon over, troops appeared everywhere at once, and artillery paraded the streets ostentatiously all night. A few shots were heard now and again, but by 8 p.m. the band was playing the “Cake Walk ” and other cheerful music in the park, and the less timid part of the population went out to listen to the strains.

[ page 218 ]

For over a year the Erivan province had been in a state of ferment, first on account of the Kultur-Kampf between the Russian Government and the Armenian Church, and later on account of the Armeno-Tartar feud. While Prince Nakashidze was Vice-Governor there had been the beginning of an outbreak, but it came to nothing. There was a small pogrom in March, 1905, and a second on June 5th and 6th, in which over fifty people had been killed. A number of incapable generals and officials had tried in vain to restore order, until Count Vorontzoff-Dashkoff commissioned Prince Napoleon, who had served for many years in the Russian army, and had recently been in command of the cavalry division at Tiflis, to take charge of the unruly district. His predecessors had, on the usual bureaucratic system, always done the wrong thing in the wrong way, and in their zeal to carry out Prince Golytzin's policy, had made war on the Armenians and secretly encouraged the Tartars to attack them ; then they found that the Tartars had got out of hand. Prince Napoleon acted differently, and exercised great severity in repressing outbursts, but also absolute impartiality. Since his arrival Erivan itself had been peaceful, but there had been trouble in the Zangezur district between Nakhitchevan and Shusha. After the Shusha fighting 8,000 Tartars, together with 1,200 Kurds of the Zangezur district, and 500 from over the Persian frontier, attacked Gerussi and other Armenian villages. On the 6th of September they had a sharp encounter with the Cossacks at Alikuliksend; a party of Cossacks had gone to Minkend to protect the Armenians,

[ page 219 ]

but on being assured by the Tartar mayor and the pristav that there was no danger, went to Khan-sovar, which was being attacked. As soon as they departed the Tartars fell on the Armenians, killing 140 and wounding 40, before the eyes of the pristav, who did not interfere. Prince Napoleon made a rapid tour through the disturbed district, visiting Gerussi on September 13th, accompanied by a small mounted force, restored order for the time being, and wrote a report to the Viceroy, in which he stigmatized the Tartars and severely blamed several district governors and officials. He had now come back to Erivan, when the riots broke out here also, for the third time this year.

It was the 1st of October, a Sunday, and being a fine day, numbers of Armenians had gone out to picnic in the vineyards outside the town and wile away the hot hours eating grapes and drinking wine. Unfortunately they imbibed too much strong liquor, became lively and reckless, and began to play with their rifles—no one dares venture outside the walls unarmed. A group of Tartars with a cart happened to be passing by, and the somewhat inebriated Armenians proceeded to fire at them. One Tartar was killed and a second severely wounded, whereupon the survivors fled, carrying the dead man and the wounded one with them (Tartars never leave their dead behind, for it is considered shameful that the giaours should see that one of the Faithful has been killed). The corpse was taken into Erivan and exposed in the Tartar bazar, as was done with that of Babaieff at Baku. This spectacle aroused the

[ page 220 ]

Mohammedans to fury, and they determined to avenge their murdered brother by a general massacre of Armenians. At about five o'clock a number of them armed with revolvers and kinjals rushed down to the boulevard, a wide open space in the middle of the town, shaded with large forest trees, where Armenians were disporting themselves peacefully in their best Sunday clothes, ignorant of what had occurred in the vineyards. A violent dispute between Tartars and Armenians broke out, and insults and accusations were bandied about. A Tartar was the first to discharge his revolver, and then the fat was in the fire, and bullets began to fly in all directions, under the very windows of the hotel where Prince Napoleon was residing. The shooting must have been somewhat wild, for although some fifty or sixty shots were fired, only half a dozen men seem to have been hit. In the meanwhile the sound of firing aroused the rest of the town, and wherever Tartars and Armenians met shots were exchanged, and several people were killed. The affair might have developed into a serious outbreak, accompanied by a heavy death-roll, but for the energy of Prince Napoleon. As soon as he heard the shots, and saw from his windows what was up, he called a couple of aides-de-camp, descended into the street, and visited on foot all the parts of the town where there was fighting. He had, however, taken the preliminary precaution of issuing orders to his troops, ever since his arrival at Erivan, that the instant trouble broke out they were to occupy certain points of vantage, so that each detachment took up its prescribed position at once.

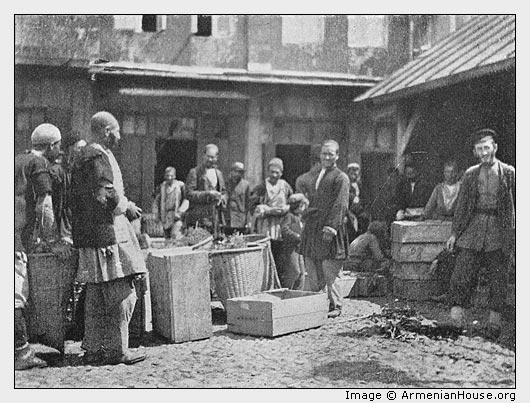

[ To face page 220 ]

[caption] Erivan. Tartars in the Bazar.

[caption] Erivan. In the Bazar.

[ page 221 ]

The Prince inspected the infantry gathered in the square near the Russian Church, and delivered them a speech in which he ordered them to shoot any one whom they saw firing, or who, being-armed, refused to give up his weapons at the first summons. “ And when you shoot,” he concluded, “shoot to kill, and not merely to frighten.” The artillery was brought out with orders to demolish any house from which shots were fired, but its services were not needed. All night it rumbled about the streets, and this was its chief function. But by five o'clock all was over, and only a few stray shots were heard in the night. Thus with a little energy and foresight, and strict impartiality, order was, restored in a few hours. The whole affair forms a striking contrast to what occurred in other places, where bungling generals and fatuous officials allowed small émeutes to develop into alarming disturbances. The next day the shops remained closed during the morning, but in the afternoon, one after another, the iron shutters began to go up, and on the second day after the disturbances the town resumed its normal aspect.

When the interest caused by the outbreak had subsided, I had leisure to explore the town of Erivan. It is certainly one of the most lovely spots in the Caucasus. The splendid view of Ararat, which one enjoys from almost every elevated spot or open space, is alone enough to entitle it to a high place among beautiful cities. The giant mountain dominates the whole town, the whole countryside. The finest point of view is from the terrace of the residence of the Armenian bishop, for one sees it rise up beyond a

[ page 222 ]

foreground of delightful vineyards and well-watered hillsides, the famous gardens of Erivan. The history of the town goes very far back. According to local tradition it was built, like Nakhitchevan, by Noah soon after the Deluge. It is first mentioned by reliable authorities in the IX. century, but it probably existed already in the VII. From the XVI. century onwards there are frequent allusions to it, for it was a perpetual bone of contention between the Turks and the Persians, each of whom held it and lost it in turn. At the beginning of the XIX. century it belonged to Persia, and the first attempt which the Russians made to capture it, in 1804, failed. But in 1827, during the Russo-Persian war, General Paskievich shelled it, and then marched in without much difficulty—whence his title of Erivansky.

The population is about 28,000, almost equally divided between Tartars and Armenians. The former are the richer of the two races, and own large estates in the district, but hoard their wealth ; the latter carry on trade. The prosperity of the Erivan depends on the agricultural products of the neighbourhood, of which wine and cotton are the most important. There is a brandy factory belonging to an Armenian. The town is also a centre of trade from various parts of Russia, Armenia and Persia.

Erivan is thoroughly Oriental in character, although since the Russian occupation many new houses have been built. There is a long, broad, dusty street, the Akstafievskaya, which starts from the boulevard and follows a north-easterly direction, ascending towards a hill flanked by two-storied houses, mostly of the

[ page 223 ]

usual Russian style. South of the boulevard is the Orthodox Church, a hideous stone structure adorned with bulging domes, and then a wide open square with rows of booths on one side and low garden walls on the other. Here the market is held, and there is a constant passing to and fro of country carts, cabs, and men riding smart little Tartar horses, which are here much handsomer than the smaller mountain ponies of Georgia and the Central Caucasus; following the continuation of the Akstafievskaya we ascend a picturesque street of Tartar shops to another market-place, where groups of camels are usually to be seen. From the first market-place a number of narrow lanes lead into the Tartar bazar, a rabbit warren of dark entries and cut-throat dens. An inveterate collector might no doubt unearth some curios out of these gloomy and ill-smelling depths, but I could see nothing of a tempting nature, and the bazar seemed poorer than others I had visited. But the vaulted passages themselves, redolent of all the mysteries of the East, with their dark curtained shops, the crowds of Tartars clad in long blue tunics, and the green turbans of the mullahs passing up and down, are very attractive. In one small open room I came upon a teacher imparting religious instruction to about a dozen little boys; he was droning out his lesson in a sing-song, monotonous voice, swaying to and fro. In another den a barber was shaving a victim to his last hair. At every turn were coffee and tea stalls, but those strange and delicious sweetmeats of the East which I had tasted at Constantinople and Sarajevo were not to be found.

[ page 224 ]

In queer galleries and tiny courts huge ungainly camels were reposing. Then through the foul-smelling bazar you come out suddenly on the great mosque called the Gok Djami. It is a good deal more than a mosque ; it is a long quadrangle containing several places of worship and a number of cells, schools, and offices of the Moslem religious administration. It is not very ancient, having been built by Nadir Shah in the XVIII. century, but it is handsome. It is devoted to Shiah worship, although in the past the Erivan mosques changed from Sunni to Shiah and from Shiah to Sunni according as the town was held by Turkey or Persia. The entrance is through a doorway flanked by a minaret adorned with coloured tiles, leading into a large rectanglar court round a garden of quite Arabian Nights’ fascination. In the middle is a pool surrounded by immense elms casting deep shadows over the tranquil water. Stately, dignified Mohammedans in flowing robes walk slowly about or sit by the side of the fountain, drinking tea and smoking long pipes. At each end of the quadrangle is a mosque ; the one nearest the bazar entrance is the larger of the two. It is surmounted by a tile-covered dome, and the interior is also adorned with beautiful Persian tiles and paintings of arabesques interlaced with human figures and animals. The front, however, being open to the court and the floor on a raised platform, the general effect is that of an open-air café concert. The smaller mosque at the opposite end is similar in plan, and the paintings are even finer. Along the two sides of the quadrangle are rows of cells where the mullahs and imams reside.

[ To face page 224 ]

[caption] Erivan. In the Courtyard of the Mosque called Gök Djami.

Photo by J. Gordon Browne.

[ page 225 ]

Each apartment consists of a group of two or three cells, as bare as possible, with no furniture, but one or two rugs and a divan which is part of the structure. The only light is admitted through the door on to the court. On leaving the mosque I approached the minaret, and knowing that there would be a fine view from the top, I asked an old muezzin to show me the way. This he was rather reluctant to do, but he eventually found the key and opened the door. With difficulty I ascended the narrow, winding stairs (I often wonder if there are any fat muezzins), and admired the view from the summit. My guide was obviously in a state of nerves ; he stuck closely to one side of the balcony and tried to prevent me from going round to the other. The reason of his anxiety, he explained, was the fact that there were some Armenian houses close by, and that the sight of a Tartar on the top of a minaret might prove an irresistible temptation for a pot-shot. However, we re-descended unharmed, much to the guide’s relief.

Just outside the town there is another interesting building, the Palace, or rather Kiosk, of the Sardars (governors). In Persian times the Shah’s representatives at Erivan were very great and powerful officials, and usually spent their summers in this little building, which is in a cool situation. Here was once an important suburb of the town, with a fortress, a mosque, and several other buildings. The mosque is still partly standing, and is adorned with handsome frescoes and tiles, now unfortunately falling to pieces. The whole group of buildings are being allowed to go to rack and ruin for want of a little care.

[ page 226 ]

When I had inspected the ruins, and—tell it not in Gath—picked up a few fragments of tiles, my cabby drove me across several walls, over the remains of a tower, down into a moat, to the Palace of the Sardars. This building is in somewhat better repair, but it too is neglected. It is quite small, a little gem of Persian architecture; it consists of one large central hall occupying the whole width of the building with three or four small rooms on each side, beautifully proportioned and decorated with charming designs, for the most part faint and faded but bursting out into bright colours in places, like half-forgotten dreams. The vaulted ceiling is covered with a number of tiny little panes of looking-glass, the favourite form of decoration in a wealthy Persian house ; there are also some portraits of famous men. Wood-carving, painted and gilt, covers the walls and doors, still almost intact. The windows have wooden trellis shutters to keep out the burning sunlight. Erivan is built on raised ground round which the river Zanga has cut a tortuous channel with precipitous sides. The Sardarsky Dvorietz, as the Russians call the Kiosk, is on the very edge of the cliff, and overlooks the river and the road far below. Here the old Persian governors lived in luxurious ease, gazing across the river to the vineyards and orchards extending for many miles, then to the plain, and beyond that again to the great and glorious mountain. It reminded me of the palace of the khans at Bakhtchi Sarai, and although much smaller, less magnificent, and in a far worse state of preservation than the stately residence of the

[ page 227 ]

Crimean princes, it has the same old-world Eastern charm.

There are few other sights to see in Erivan. The streets are mostly narrow, tortuous lanes, between mud walls above which trees appear. There is vegetation everywhere, and cool runnels in almost every street. The flat roofs, on which the inhabitants spend the evenings and sleep during the fierce heat of summer, are characteristic. But there are also some handsome houses belonging to rich Armenians, well-built and luxurious, and surrounded by pleasant gardens.

But there are many interesting people in the town, among whom I may mention Karapet Vardapet * Ter-Mkrtchian, the Eparkhialny Nachalnik or acting Bishop of Erivan. Beyond the bazar on raised ground is a group of buildings surrounded by a wall forming what one may term the close. There is the Armenian Cathedral—an edifice of no great architectural importance—the episcopal offices, and residences for the bishop and a few priests. The bishop's house is an unpretentious building one storey high, with a veranda giving on a sort of garden within the enclosure, and another broad terrace looking straight across the plains to Mount Ararat. The bishop himself, Father Karapet, is a largely built man, tall, stout, evidently of great strength, not much over forty years of age, handsome and intelligent-looking. He wears a long black robe and a tall black cap, somewhat like that of Greek bishops, on which

-------

* The Vardapets are monks and doctors of theology. See next Chapter.

[ page 228 ]

he places a large flowing hood when he goes out. In his hand he carries a large silver-topped walking cane. Everything about him is large, stately, and dignified. He is a good specimen of the Armenian higher clergy, and is very cultivated. He was educated first in the seminary at Etchmiadzin, and later at the Berlin University where he was a pupil of Professor Harnack. He talks excellent German, as well as Armenian and Russian, and is the author of several publications, some of them in German and highly appreciated in German learned circles. But he told me that for ten years he had not been able to devote any time to study, for the whole of his attention had to be spent in pastoral duties and in visitations to places where his people were in conflict with the Russian authorities over Church and school questions, or where they were at war with the Tartars.

I also called on Count Tiesenhausen, the Governor, a typical Russo-German bureaucrat, polite and friendly, but unwilling to talk politics from fear of compromising himself. He was evidently very suspicious, and trusted neither the Tartars nor the Armenians, and wished to avoid taking a definite line of his own, which was all the easier for him now that Prince Napoleon as Governor-General had full responsibility. All I could get out of him was that the Armenians accused the Tartars of being in the wrong, while the Tartars accused the Armenians —both of which facts were not unknown to me. I was even less fortunate with Prince Napoleon. Although I had the honour of occupying a room

[ page 229 ]

next to that of His Imperial Highness, I did not succeed in obtaining an interview, as the Prince was afraid lest his words “should get into the papers.” I had a talk with his Chief of the Staff, Colonel von der Nonne, an agreeable, intelligent officer, who willingly gave me all the information I desired, and even let me read the Prince's official report to the Viceroy on the recent occurrences. I may mention that at least on this occasion the official report was borne out by all the information I could obtain from private sources.

I then made the acquaintance of some Armenian notables, one of whom held a minor Government post. His official connection, however, did not prevent him from abusing the policy of the Russian Government nor from speaking of the Tartars with great bitterness. He was otherwise a mild little man, kindly and hospitable, and although less intellectual and cultivated than some other Armenians I have met, and not wealthy, he had managed to send his son to the University of Kieff, and his daughter to that of Zurich. “ The conditions here,” he said to me, “are terrible. If I could only afford it, I should like to sell everything I possess and go right away to Europe and live in peace.” At his hospitable board I met several other Armenians, including a priest from Asia Minor, who after dinner sang the war-song of Antranik, the leader of Armenian revolutionary bands in Turkey. It was interesting and by no means inharmonious, but most melancholy for a war-song. I could not converse with the priest as he only knew Armenian and Turkish. I found

[ page 230 ]

that the Erivan Armenians speak their own language much more than those of Tiflis or Baku, and use it in preference to Russian. Dr. Tigraniantz, another highly cultured Armenian whom I met at Erivan, was a most charming and intelligent man, about sixty years old, belonging to one of the most notable families in the country. He had studied, like so many other Russian-Armenians, at the ex-German University of Dorpat in the Baltic provinces.

I spent a pleasant afternoon the last day of my stay among the famous fruit gardens of Erivan. The town is in the midst of an oasis of vineyards and orchards beyond which lies the arid plain, and the fertility of this district is celebrated throughout Armenia. The particular property which I visited belongs to a rich Armenian named Afrikian. Having inherited a large wine-growing estate, he had studied scientific horticulture at Klosterneuburg, near Vienna, and in South Tirol. On returning home he had introduced all the latest improvements into his property, which was now exceedingly valuable. These orchards are delightful retreats during the hot weather. The soil is stony and arid, but an elaborate system of irrigation has been established, so that the whole belt of vineyards is intersected with tiny runnels. M. Afrikian has built himself a large and comfortable country house, on the terrace of which we spent a pleasant quiet hour eating unlimited quantities of grapes and peaches, and drinking excellent wine, the best I have tasted in the Caucasus. These Erivan grapes, called kiskmish, are a delicious memory; small, seedless, with an exquisitely sweet flavour,

[ page 231]

one could go on eating them for ever. You do not eat them one at a time as you do other grapes, but put half a dozen into your mouth at once ; it may be greedy, but it is very nice all the same. And the peaches ! Who can do justice to their scent, their taste, their colour, their luscious softness ? We were also taken to see the wine-cellars, cool vaults stocked with huge vats, the winepresses fitted up with modern machinery, the chemical testing appliances, and all the other details of a well fitted up wine factory. My host was pleased to have an opportunity of airing his German, in which he discoursed regretfully of his happy days in the peaceful Austrian valleys, in a land where order is established and life and property secure.

It was difficult to imagine here, under these cool, green bowers, amidst these heavy laden vineyards and peach-trees, where stalwart Armenian peasants were employed among the peaceful labours of the field, that we were in a land of fire and sword, that at any moment the silence might be broken by shots, and that a column of smoke might rise from burning farmsteads. But all remained silent and undisturbed, save for the songs of the peasant at work.

Table of contents

Cover and pp. 1-4 | Prefatory

note | Table of contents (as in the book)

| List of illustrations

“Chronological table of recent events in the

Caucasus”

1. The Caucasus, its peoples, and its history

| 2. Eastward ho! | 3. Batum

4. Kutais and the Georgian movement | 5. The

Gurian “republic” | 6. Tiflis

7. Persons and politics in the Caucasian

capital

8. Armenians, Tartars, and the Russian government

9. Baku and the Armeno-Tartar feud

| 10. Bloodshed and fire in the oil city

11. The land of Ararat | 12. The heart

of Armenia | 13. Russia's new route

to Persia

14. Nakhitchevan and the May massacres

| 15. Alexandropol and Ani

16. Over the frosty Caucasus | 17. Recent

events in the Caucasus | Index

| Acknowledgements: |

| Source:

Villari, Luigi. Fire and Sword in the Caucasus by Luigi Villari author

of “Russia under the Great Shadow”, “Giovanni Segantini,”

etc. London, T. F. Unwin, 1906 No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed by any means without written permission of the owners of ArmenianHouse.org |

| See also: |

| The Flame of Old Fires by Pavel Shekhtman (in Russian) |